The material stuff of dirt and plastic, stains, and insects, flowers and clouds, surrounds us all the time, but how often do we actually see these things? We spend most of our days cleaving the foreground from the background, stumbling through our human lives, convinced we are separate creatures, disconnected from a larger whole. What brings us back from the confused and isolated condition of being human? In a word: attention. Christian mystic Simone Weil equated attention with love and prayer:

The quality of attention counts for much in the quality of prayer . . . Attention consists of suspending our thought, leaving it detached, empty and ready to be penetrated by the object. (1)

To be moved by an object, even if it is a twisted piece of twine lying on the pavement, is what seems to lie at the heart of these photographs by Victoria Mara Heilweil. Like prayer itself, her daily practice of walking through the same ten blocks of her Mission District neighborhood created a constraint and a cauldron for something new, something intimate and wholly unexpected. In doing so, Heilweil changed her photographic practice. As she says, I could not longer plan ahead for what my content would be. Instead, she had to trust the world. Which means she had to return to the world on its own terms. Much like the 9th century Zen monk Dongshan taught his disciples: Just This. (2)

Dongshan’s phrase underscores a basic tenet of Zen Buddhism: spiritual practice does not involve getting something new, but rather taking care of what we already have. Like Heilweil, he is asking us to pay a different kind of attention.

But in our age, paying attention this way can feel like a radical act. For all its benefits, our digital world tends to distract, rather than focus our gaze. It also trains our brains to seek constant stimulation and experiences of divided attention rather than sustained open awareness to what is present. As I type the period that ended that sentence, a ping from an email entering my inbox lifts me out of one thing with the promise of something else. Always the promise but never the presence. And this pattern repeats itself, over and over again.

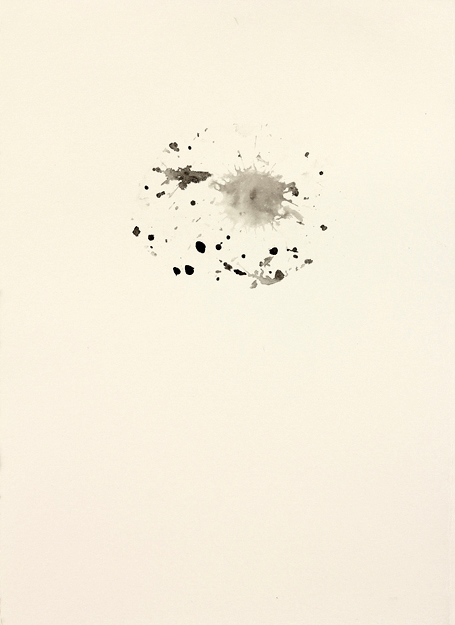

So, when a photographer takes up the call to pay attention each day to the beauty lying in plain sight in her own neighborhood, we should turn off our screens and take a look. In Heilweil’s images the world begins to reveal itself in new ways. Much of what she captures is the residue of daily gestures-- life coming into being and then passing away. A torn scrap of handwriting, an empty glove, an un-named stain, the fragile shape of four pine needles resting on the sidewalk. These visual haiku startle with their beauty even as they mystify us with their meaning.

Within these 166 images we also find coincidences of composition. Suddenly objects seem to be in conversation with each other. A blue vinyl glove delights in the murmur of fallen leaves, a crushed plastic cup drags its shadow across the green crack in the sidewalk; the word zest from an old soap wrapper speaks to the withered visage of a dead leaf. None of these vignettes can be explained by the closed loop logic of an isolated self. Instead, the mind that knew the world before it went on this particular walk, is suddenly freed of its old conceptions. As we pay attention with Heilweil, as we walk with her, we allow the world to come to us. In these images we enter a more mysterious landscape of syntax and rhythm, echo and possibility.

It is precisely that mystery, that not-yet-known quality that delights us in these pictures. In a famous Zen story, two teachers meet on the road, and one is carrying his bags:

Where are you going?”, inquires the first teacher.

“I’m going on a pilgrimage”, the other teacher responds.

“What’s the purpose of pilgrimage?” asks the first teacher.

“I don’t know.” he responds.

“Not knowing is most intimate.” replies the first teacher. (3)

Not knowing is most intimate. No wonder that mystery is such an important part of beauty. It’s what enables beauty to sit side-by-side with some of the darkest parts of our world. When we think we know everything about what life is, when we are convinced that the world is just one way, either beautiful or dark, life loses its magic, and we lose our capacity to see what is really in front of us.

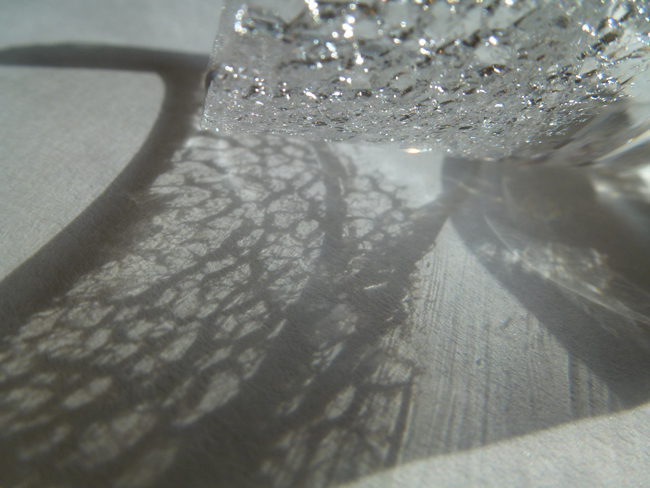

Paying attention, as Heilweil does on these daily walks, expands our awareness and opens a space beyond our limited view. In this way, we feel ourselves embroidered back into the world. In one of her pictures, the dark shadow of a tree spreads across the face of a blank wall. A familiar darkness set against the dying light. But then we see the crenulated shadows of the tree’s leaves are in fact exact replicas of the curly-edged hair of the photographer. Heilweil’s own shadow has entered the frame and completes the composition. As philosopher Elaine Scarry writes:

At the moment one comes into the presence of something beautiful, it greets you. It lifts away from the neutral background as though coming forward to welcome you—as though the object were designed to “fit” your perception. . . Your arrival seems contractual, not just something you want, but something the world you are now joining wants. (4)

If love is the quality of one’s attention, then paying attention helps us fall back in love with the world.

Notes

(1) Weil, Simone, Waiting For God, Fontana Books, 1959, pp. 66, trans Emma Scott, 1959.

(2) Book of Serenity, Case 49, p. 206, trans Thomas Cleary, Shambala, 1998.

(3) Book of Serenity, Case 20, p. 86 trans Thomas Cleary, Shambala, 1998.

(4) Scarry, Elaine, On Beauty and Being Just, p. 25, Princeton University Presss, 1999.